The tremor started in my left pinky finger. It was subtle at first—a tiny, rhythmic twitch that I laughed off as too much caffeine. But then came the stiffness in my shoulder, the mornings where my feet felt glued to the floor, the handwriting that shrank into microscopic scrawls.

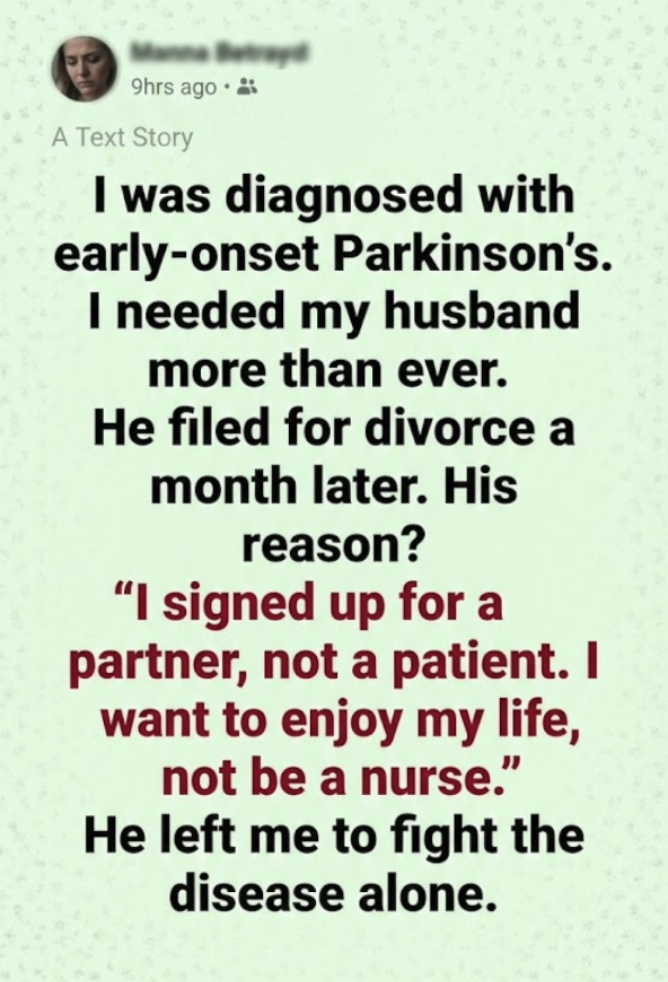

The neurologist’s office was cold and smelled of antiseptic. Dr. Aris didn’t sugarcoat it. “I was diagnosed with early-onset Parkinson’s,” he said gently, handing me a pamphlet that felt heavy as a brick. I was thirty-four.

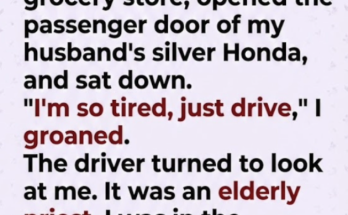

The world tilted on its axis. I sat in the car afterwards, gripping the steering wheel to stop the shaking, and called my husband, Greg.

“I need you,” I whispered. “I needed my husband more than ever.“. I needed him to be the rock he promised to be at the altar. I needed him to tell me that we would fight this, that a diagnosis wasn’t a death sentence, that we were a team.

For the first few weeks, he went through the motions. He drove me to the pharmacy. He cooked dinner twice. But there was a distance in his eyes, a glazing over whenever I talked about medication schedules or physical therapy. He stopped touching me. He started working late.

Then, exactly thirty days after the diagnosis, he sat me down at the kitchen table. He didn’t have a glass of water for me. He had a manila envelope.

“He filed for divorce a month later,” I realized, staring at the papers.

“Greg?” I choked out. “What is this? I’m sick. You can’t leave me when I’m sick.”

He looked at me, and for the first time, I saw the utter shallowness of his soul. He wasn’t sad. He was annoyed. He looked like a man who had bought a sports car only to find out it had a transmission leak, and now he just wanted to return it.

“His reason?” He didn’t even try to soften the blow.

“Look, Sarah,” he said, leaning back in his chair. “‘I signed up for a partner, not a patient.’“.

The air left the room. The vow “in sickness and in health” apparently had a fine print clause I had missed: Terms and conditions apply; offer void if sickness is inconvenient.

“‘I want to enjoy my life, not be a nurse,’” he continued, as if my illness was a personal affront to his weekend plans. “I want to travel. I want to go hiking. I don’t want to spend my forties pushing a wheelchair.”

“I’m not in a wheelchair, Greg!” I screamed, my hand trembling violently now. “I’m still me! I’m just… I have a challenge. We could face it together.”

“I don’t want a challenge,” he said coldly, standing up. “I want a wife who works. Goodbye, Sarah.”

He left me to fight the disease alone.

He packed a bag and walked out the door, leaving me in the silence of a house we had bought together, with a disease that was slowly stealing my body.

For a week, I lay in bed, wishing the earth would swallow me whole. I was terrified. Who would help me button my shirt when my fingers wouldn’t work? Who would catch me if I fell?

But then, a strange thing happened. The fear burned off, revealing a core of steel I didn’t know I possessed. I looked at the empty side of the bed and realized something vital: Greg hadn’t been a partner. He had been a passenger. And passengers are useless in a storm.

I stood up. I made myself coffee, spilling half of it, but I drank the rest. I called a support group. I called a lawyer.

Greg wanted to “enjoy his life”? Fine. Let him go chase his hollow pleasures. I had a bigger battle to fight. I realized that the tremor in my hand was the only thing shaking; my resolve was rock solid. I didn’t need a nurse who resented me. I needed a warrior, and looking in the mirror, I saw that the only warrior I needed was already looking back at me.